I first read Gabriel Garcia Marquez in high school; I was sixteen or seventeen, I’m not quite sure. We focussed on South American literature in the studies leading up to my final year. Between Pablo Neruda’s love poems and Isabelle Allende, was a man named Marquez. The book, One HundredYears of Solitude, with its mountainous cover and silver spine. Or maybe it had an orange spine? Memories get lost and mixed up about the cover but not the content. I wrote notes upon notes on that book, lost in the town of Macondo and the incessant cycles that doomed the generations of the Buendia family.

I still have my notes on One Hundred Years of Solitude; I wrote out each quote I loved into an orange and black striped notebook. I scrawled on the front “You are looking at a national treasure” in ballpoint caps. The subject: 100 Yrs, English stuff. The school: OF LATIN AMERICA. “This is mine,” etched above the 128 page note.

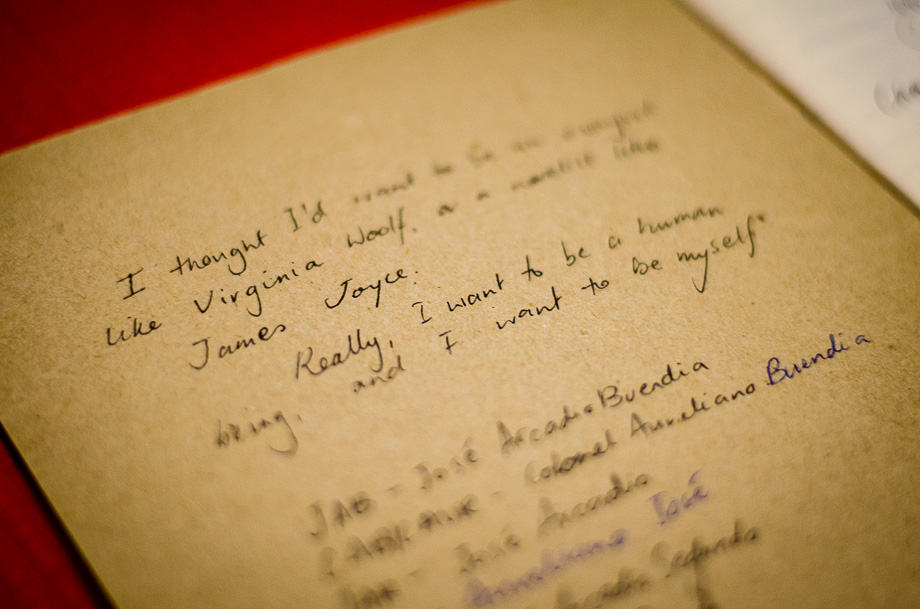

On the inner cover, I had written in my uneasy cursive:

I thought I’d want to be an essayist like Virginia Woolf, or a novelist like James Joyce.

Really, I want to be a human being, and I want to be myself.

Below, a list of abbreviations of the family members. Page after page of quotes, notations about gypsies and lovers. Poorly translated prints of the only available biographical information on the internet, long before Wikipedia.

Flicking between the family tree at the front, determining which of the Arcadios and Aurelianos was being written about, I fell in love with the style of Marquez. A girl from Penrith who had never heard of magic realism, but could only hope to dream about another world, stuck as I was in a private school wearing navy blazers and eating sandwiches for lunch. What was this place, Colombia, where yellow flowers rose into the sky, where words were compared to the hanging of washing on the line, where insomnia caused people to forget the meaning of language?

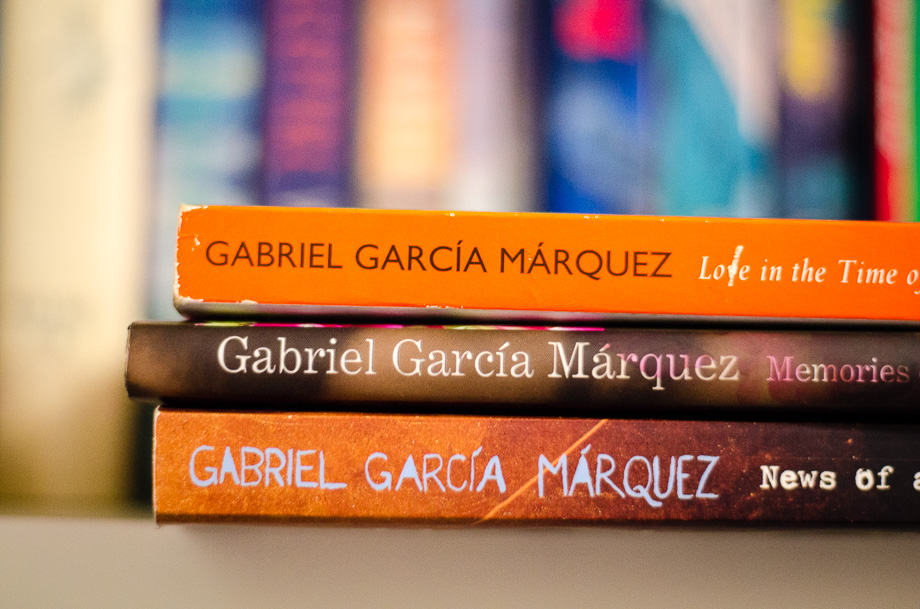

I read his other works over the years, so struck was I with the way he captured passion and love. Did anyone look at me sideways reading Memories of My Melancholy Whores? Or the way I cannot eat almonds and not think of the scent after Love in the Time of Cholera.

When I heard the news of his death I was on my way to church, sitting at a grim train station that had nothing of magic and everything of realism. My love turned to me and said, “Gabriel Garcia Marquez is dead.” And I wept a tear or two, turning my face away from his. I wonder what people thought of that young but not so young woman crying on the train station on Good Friday morning. I was weeping for a man I had never met, yet someone who taught the greatest of lessons through words.

Marquez taught me the most valuable lesson about literature at the time I was most ready to be influenced in my beliefs. In those late teenage years, before true adulthood sediments our thoughts, at a time when hearts break more easily and passions are not easily quashed by realism.

Marquez taught me that reality is lost, when the meanings of words are forgotten. He taught me that time passes, but not so much. He taught me that the value of a book is greater than the comfort of a man. His books did what they taught; by urging me out of loneliness and solitude through literature, I became a human being, and I became myself.

Share your thoughts