What do sexy lamps, refrigerators and underwear have in common?

They’re all tests for authentic female characters.

There’s nothing more frustrating as a female reader than reading a story without authentic women. Even the wrong undies can throw me out of a story (or send me into fits of giggles).

Before I list mistakes, I need to say that there is no universal experience of womanhood, and a lot of these issues listed below come from writing female characters based on archetypes. There’s no one way to be a woman, but there are a LOT of cultural expectations around how women should act, which makes writing female characters complex and challenging. Like any good character, really. Having said this, I acknowledge I’m writing in generalisations about the female experience.

And while this might seem like a post skewed towards male writers, it comes from a genuine place of wanting to see authentic female characters. So I hope you’ll embrace these serious, not so serious and downright funny mistakes, and in doing so, learn how to write better female characters.

Which leads me onto my number one pet peeve of all time…

Your character checks herself out in the mirror and thinks she looks hot

Have you ever read a book where the woman stops in front of a mirror, checks herself out, and thinks she’s smoking hot? Or she randomly looks down her shirt to check out her breasts, and finds them surprisingly attractive, perhaps comparing them to an item of food?

Yes, women examine their bodies in the mirror. But when a woman looks in the mirror, the focus is often on insecurity, not confidence. Few women just check themselves out and go yep, I’m hot. We’re more likely to think about cellulite and sagging breasts, grey hairs and flab.

Women have complex relationships with their bodies because of being brought up in an appearance driven culture. Write this into your character’s self-perception.

The woman is only a sexual being

Does your female character only relate to people through sex? She knows she looks hot (because she looked in the mirror) and she uses her hot bod as a weapon of seduction and manipulation to get what she wants. This is fine in a book. HOWEVER, she might be a femme fatale, but it shouldn’t be the totality of her character. She is not a fembot.

If you have a male protagonist, examine how the female characters in the book relate to him. See if they are only ever described as a sexual object, or their discussion with him is only about sex or leading to sex. Even if he is James Bond. Use the Sexy Lamp Test (one of my favourite feminist tests) to determine whether your female character can be taken out of the plot and replaced with a sexy lampshade.

If you’d like to see an excellent example of breaking down this trope, check out Ed Brubaker and Sean Phillips’ Fatale, which gives the femme fatale both agency and horror at her perpetual fate to ensnare men.

The woman acts only as a plot function to accelerate the male plotline

You might have heard the term ‘fridging’ bandied about. “Women in refrigerators” is a term created by writer Gail Simone, referring to a now infamous comic where Green Lantern comes home to find his girlfriend stuffed into a fridge, kicking off his own personal journey for justice. You’ll hear a cry of ‘fridging’ whenever violence is committed against women to accelerate a man’s story arc.

It’s a common occurrence in crime novels, where a dead, nameless woman is found in a lonely place, and a male investigator makes it his mission to find the killer. She’s never given agency.

A great storyteller will take this trope and turn it on its head. How can people without agency be given agency? These are uncommon stories that need to be told.

The women only relate to other women through the prism of men

Another great test you might have heard of is the Bechdel Test. The requirements: two named women must talk to each other about something besides a man.

There are discussions about the efficacy of the Bechdel Test, but I find it a great litmus test to think about my writing. Yes, as a woman, I still fall into the trap of writing stories where women do not talk to each other, or where they relate to each other only through the prism of a man.

Use your discretion – for example, I write a lot of crime, and if a female investigator and female coroner are discussing a male victim, I still perceive this as good representation, as they’re discussing the man in the course of acting as professionals.

A perfect example of a story where women relate to each other in earnest and realistic ways is Greta Gerwig’s spectacular interpretation of Louisa May Alcott’s novel Little Women. Or watch the excellent TV show Call the Midwife. Both of which blow the Bechdel Test out of the water.

The woman lacks agency

Leading on from the Bechdel and Sexy Lamp Test, there are a plethora of stories where a woman is included but not given agency. What do we mean by agency? Agency is about a character having the capacity to make meaningful and independent decisions that contribute to the story. When a female character becomes passive and accepting of all decisions made for her, we relegate her to sexy sidekick status, and it reads more like a 60s pulp novel.

There’s only one woman (or none)

Unless this is the Smurf village, there needs to be a REALLY good reason there’s only one woman in the whole story. Even if this is a historic war story, there were countless women who took part in modern warfare, even on the front lines. Nurses, photojournalists, and surely, the women who disguised themselves as men, not to mention all the historic examples of female soldiers, warriors and leaders who led their armies as women.

Not writing women into stories is lazy. The only time I can think of it as acceptable is in scenarios where there is a very strict division on gender, such as an all-male prison. Even then…

A book which does this brilliantly is Patrick Ness’ The Knife of Never Letting Go, one of my all-time favourite books. And for a good laugh, check out Terry Pratchett’s classic, Monstrous Regiment.

The female characters don’t have a network of friends and family

Most people like to have friends, regardless of their gender. Women especially rely on a complex support network of friends and enjoy shopping, travelling, chatting, going for coffee, taking down evil, hunting criminals etc. with said friends.

So, to have a female character who doesn’t have any female friends, and only relates to men through the book is strange. If this is the case in your book, there needs to be a reason for it – she might have social anxiety, she might work in a male-dominated industry. She will probably still call her mum.

The underwear is wrong or non-existent

I can’t tell you how hilarious it is to play a video game or read a book and someone gets the underwear wrong. Women need bras. If your character is wearing a backless dress, she’ll need a stick-on bra or tape. If she’s out running for her life, give her a damn sports bra!

As for the bottom half, women don’t wear stockings and panties and suspenders and stay-ups all at the same time. If she’s out fighting crime, she is not, I repeat not, going to be wearing sexy lingerie under her work uniform. Even Angel Dare, Christina Faust’s ex-porn star investigating her own abduction, discusses her underwear as an aspect of character in Money Shot.

Her clothing and footwear are inappropriate for the situation

Nothing illustrates this more than the film Jurassic World. Trust me, running around the jungle in high heels is impossible. I tried wearing heels to an outdoor wedding after a storm, and I ended up aerating the soil as my shoes stabbed into the muck.

It hurts to wear high heels all day, which is why you see women wearing sneakers on public transport, then slipping into heels at work. It can also wreck your arch. At least, if she’s going to run in heels, give her some good boots with gel insoles.

Don’t get me started on the clothing, especially in epic fantasy novels. You know the kind. Woman in skimpy chain-mail bikini. Not gonna protect her from swords, arrows and brutal battles that go down at the end of EVERY epic fantasy novel ever.

Sure, us women want to look good, but we also don’t want to face down a dragon without a sports bra and an inflammable helmet.

The female characters don’t get periods

If you’re writing from the perspective of a female character, you must understand what stage of life she’s at, and whether she’s experiencing her period. The lack of periods is more obvious in stories that involve protracted adventures in exotic destinations and survival stories. It’s not so much of an issue if you’ve only got 24 hours to save the world!

There are plenty of websites detailing what happens when women get their period, so I’ll leave it to you to do your research, but it’s uncomfortable, affects personality and hormones, and women need sanitary items such as pads and tampons to deal with it. If your character does not get her period, there should be a good reason for this, such as she has skipped it while taking birth control or has completed menopause.

I will always remember Victor Kelleher’s Papio as one of the few books which dealt with a female character getting their period in a YA book when I was a teenager. It made me think of all the other books that hadn’t done so. You need not give a detailed description every time someone goes to the toilet, but thinking about what stage of life your character is at and how her period affects her can create a more authentic story.

Birth control and contraception is not an issue

During sex, is the woman concerned that she might conceive? What type of contraceptive is she using? Is she infertile, like Yennefer in Andrzej Sapkowski’s Witcher series? Or is she too caught up in the moment and the book will finish soon anyway, so let’s not talk about this here. These are questions that women face in relationships, so it’s important to consider your character’s attitudes to sex, pregnancy and contraception.

Conclusion

There you have it – my extremely long rant about mistakes writing female characters. In all seriousness, I hope it has been helpful to challenge stereotypes and break down tropes. I would love to know some positive examples of male authors writing female characters, or just out and out awesome representation of women in fiction. Share your recommendations in the comments below.

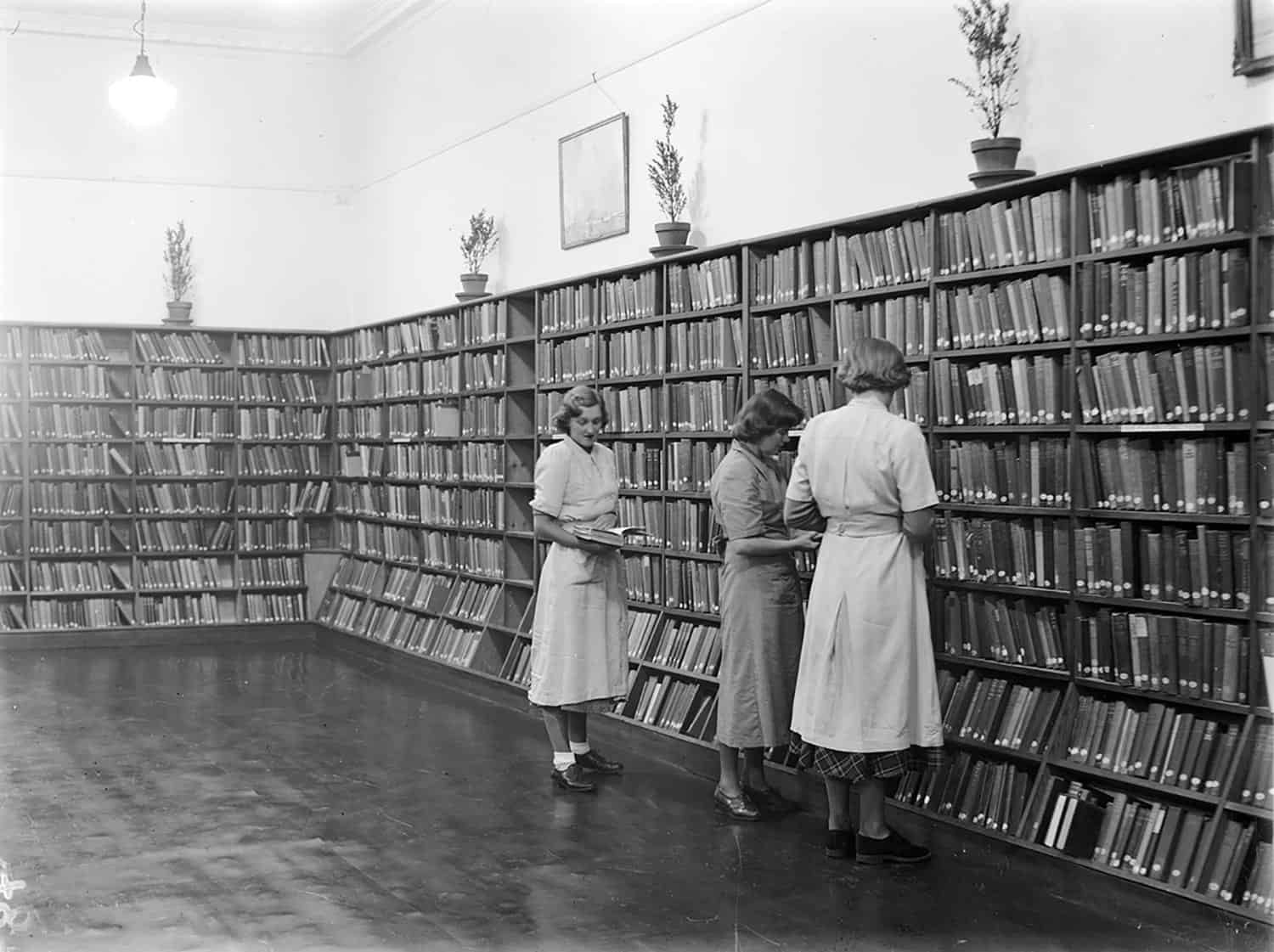

Image credits: State Library of Victoria, Public Domain

Share your thoughts